New housing project in Portland to include affordable units and first-of-its-kind 'co-op' units12/28/2023

Author: Hannah Yechivi (NEWS CENTER Maine)

Published: 12:40 PM EST December 27, 2023 PORTLAND, Maine — For many years now, the city of Portland has been looking for more affordable housing units. In the early 2000s, the Portland city council chose a number of parcels in the city to put up for competition for ideas to develop housing. Maine Cooperative Development Partners won the rights from the city to develop three out of the four housing parcels. One project site is located by the Dougherty fields, and the other two are in the North Deering area. The ones in North Deering will be a mix of low-income tax-credit apartments and "c-op" housing units. Tax increment financing (TIF) will support the proposal for Lambert Woods North, which will be 72 low-income tax-credit apartments, for families earning up to 60% of the area median income (that's around $70,000 a year for a family of four). To build those affordable housing units, MCDV has partnered with the Boston-based nonprofit developer Preservation of Affordable Housing (POAH). Cory Fellows is the vice president of real estate development for POAH. Fellows said the recently approved TIF will make a big difference. "One of the big challenges that we are seeing with affordable housing right now regardless of location is that the rents with affordable housing, you fix the rents so that people can afford to live there long-term, so your revenue from the rent side is capped, if you will. But the expenses are not, so you are still subject to increased utility costs, insurance costs have been a very big one in the industry, and local property taxes can be a big variable," Fellows said. Lambert Woods South will be a 90-unit middle income cooperative, for households earning 80% to 100% of the area median income (that's around $120,000 a year for a family of 4). A partner of Maine Cooperative Development Partners, Liz Trice, said the co-op project will be the first of its kind in Portland. "For a long time we've just had rentals where the prices tend to go up every year on people," Trice explained. "And then we have home ownership, which is really hard for a lot of people to get into, so we see that in other states there are different forms of ownership that allow people more steps up along the way. So it's kind of in between renting and owning in that it gives you cost-stable housing for a really long time but its not as hard to get into as home ownership." Trice also explained that "co-op" housing is also a way of retaining public investment in the public ownership, so as long as people live there, they get to have stable housing costs like an owner. "But they didn't have to get a mortgage at the beginning, and when they leave they don't get a windfall of increased equity," she said. "They get to get back their shared price, which is sort of like a down payment with appreciation, but they don't get to get a lot of money like if you had a bank loan." Last but not least, Dougherty Commons project by the Dougherty fields will have a little bit of everything: low-income apartments, middle-income apartments, and middle-income condos that people can buy. Last week, the Portland city council approved to support the condo project with a $1.5M housing trust fund. Trice said this whole project is one-of-a-kind. "There's a bunch of things here. One, the city putting up their own land is innovative, the fact that they specifically asked for innovative models," she said. "And on these three parcels of land we have four different types of ownership and financing, so that's a really innovating thing that we hope that by doing all the hard work we've done for the past four years, that this will make it much easier to have new housing types in the future." Original Article and Video

0 Comments

Portland Press Herald, Feb 28, 2023 - By Rachel Ohm, staff writer.

A newly approved project in Portland’s North Deering neighborhood is expected to add 162 units of affordable housing. The Lambert Woods project by Maine Cooperative Development Partners is moving ahead after the planning board’s 6-0 vote Tuesday to approve a major site plan for the project at 165 Lambert St. Chairperson Maggie Stanley was absent. The firm believes the project and a sister project being developed in Libbytown are the first limited-equity co-ops in Portland – an ownership model that proponents say boosts affordability and gives residents more say over management and costs. “The values we’ve brought to this all along are aspects of community, environment and also affordability,” Liz Trice, a partner at Maine Cooperative Development Partners, said before Tuesday’s vote. “We are sticking only with models that provide long-term affordability and we have done a ton of work to make the site really compact and preserve the surrounding forest.” The project was approved conditionally, with the board also stipulating that Maine Cooperative Development Partners comply with a handful of additional requests, including that they provide documentation from utility companies about their ability to serve the project and contribute $13,200 to the city’s tree fund. The project is expected to add an influx of much-needed affordable housing on either side of Washington Avenue Extension between Lambert and Auburn streets. . . read more and see images PORTLAND (WGME) – Many working families have been priced out of the housing market in Maine. Now, a new development project is promising hundreds of new homes in the Portland area that median-income families can afford. In 2019, the City of Portland chose four parcels of land to be developed for workforce housing. Three of those parcels now belong to Maine Cooperative Development Partners. "In a cooperative, you buy a share of the whole, and then you get a proprietary lease to live there,” Maine Cooperative Development Partners Partner Liz Trice said. “So you have stable housing costs for as long as you live there." In order to qualify, a single person must make at least $47,000 a year, ranging up to, for a family of six, $130,000 a year. "But again, those numbers are subject to change, and we'll have to remeasure them at the time people move in in 2024," Maine Cooperative Development Partners Partner Brian Eng said. With another two years until completion, the land at 57 Douglass Street is full of overgrown grass, but the area holds a ton of potential, Trice says. "Behind you is a Little League field,” Trice said. “This is going to become a new basketball court. There's a brand-new playground going over there. And then back here there are soccer fields." The Douglass location is a three-minute walk to the nearest bus stop that Eng says eases the strain of a long drive to work for some. "We've heard loud and clear from multiple employers across all different industries here in Portland, talking about how difficult it is to attract and retain talent these days because of the shortage of housing that's located close to where people work," Eng said. Between all three parcels and 200 homes, the project's estimated cost is $40 million, funded through the City of Portland and HUD, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. "We are currently waiting to hear on grants from the county and from the city,” Trice said. “And the county grants are especially important to us because that helps keep our share price low." The project is in its third week taking $500 deposits to secure a spot in line for a house. For more information, click here. wgme.com/news/local/new-development-project-promises-hundreds-homes-median-income-families-portland-maine-housing-market About half of the 120 units in Dougherty Commons in Portland will be part of a cooperative housing model in which residents will jointly own and manage the property.Renderings of the Doughtery Commons project, which will include 57 units of limited equity cooperative housing and a 63-unit apartment building of mostly affordable apartments. Rendering courtesy of Maine Cooperative Development Partners/Aceto Landscape Architects

BY RACHEL OHM, STAFF WRITER 5/30/22 A newly approved project in Portland’s Libbytown neighborhood is expected to add 120 units of housing, about half set up in a cooperative model in which residents will jointly own and manage the property. The remainder of the units at Dougherty Commons, which was approved by the Planning Board last week, will be a mix of apartments, mostly affordable, some market rate. Just over half of the total units in the project will be available at rates affordable to households earning either at or below 60 percent or at or below 80 percent of the area median income. “We’re excited about it,” said Liz Trice, a partner with Maine Cooperative Development Partners, the Portland company that is developing and will manage the cooperative housing part of the project. “We’re excited for the opportunity to do something we feel good about and that we feel will be a good model going forward.” The project, located at 57 Douglass St., came out of the city’s 2020 request for proposals for affordable housing on the former site of the West School, which was demolished in 2016. Maine Cooperative Development Partners was selected in November 2020 along with the Szanton Company, which will develop and manage a five-story, 63-unit apartment building on the site. They plan to break ground in the spring of 2023. Maine Cooperative Development Partners is working on a 57-unit limited equity cooperative made up of seven townhome-style buildings. Cooperatives are owned and managed by residents rather than landlords, and proponents say they can help create permanent affordable housing for people who don’t make enough to afford market rates. In a limited equity co-op, as opposed to a market rate co-op, the buy-in is often lower but there are also restrictions on the amount of profit residents can get from selling their shares. State law requires that homes in limited equity co-ops be affordable to households making 100 percent of the area median income, which in 2021 was $70,000 for one person and $100,000 for a family of four in Cumberland County, according to Maine Cooperative Development Partners. In addition, the city is requiring that 25 percent of the project – or 15 units – be reserved for households earning 80 percent of the area median income or less. The current cost estimate for the cooperative at Dougherty Commons is for residents to pay an up-front share price ranging from $5,000 to $30,000 and a monthly amount including utilities ranging from roughly $1,000 to $2,500 – based on the size of the unit, income of the household and the number of people in the household. “What we’ve been seeing right now for the last five years or so is that for a lot of people who would have had the opportunity to buy a home in Portland, that’s become impossible,” Trice said. “We think that’s a likely market (for our project.) Another market would be people who maybe were happy renting but now they’re realizing monthly rents are just going to keep going up and they may be forced out if they don’t do something different.” The 63-unit apartment building being built by the Szanton Company will include 46 deed-restricted workforce housing units, to be rented at an affordable rate to households earning at or below 60 percent of the area median income, and the remaining units rented at market rate. Right now, an affordable one-bedroom unit would rent for about $1,200 while a market-rate one-bedroom would be about $1,500, according to Carl Szanton, development associate with the Szanton Company. Szanton said it’s possible that some of the market-rate units in the building could be flipped to workforce units because of rising construction costs and tax credits that are available for building affordable units. “Housing in the city of Portland is in such short supply right now, so we’re really excited to build much-needed housing right in the middle of the city that will be affordable to low- and moderate-income Portlanders,” Szanton said. Zack Barowitz, a member and past chair of the board of the Libbytown Neighborhood Association, said members of the association and neighbors generally have been supportive of the project, though there have been some concerns about an overabundance of parking. The project is slated to include 78 parking spots, though Barowitz said there is ample street parking. “There are environmental concerns. It constitutes a bit of dead space and it encourages more car usage by having parking included,” Barowitz said. Ultimately, though, he said members of the association are excited about the project. “Many of the neighbors are quite pleased to have so many workforce housing units in the neighborhood, which will add to the enrichment of the neighborhood and a badly needed workforce for the city,” he said. https://www.pressherald.com/2022/05/30/libbytown-complex-with-affordable-housing-wins-approval/ As tenants organize to take over their buildings, there's been an increased interest in going the co-op route. Could the networks that support resident-owned mobile home park communities shift their focus to support residents of multifamily buildings that want to go co-op?

Image caption: Northcountry Cooperative Foundation’s Julie Martinez introduces herself to the Sky Without Limits residents at a meeting on June 2. Photo courtesy of Victoria Clark, via Northcountry Cooperative Foundation By Meir Rinde - Originally published in https://shelterforce.org/2021/08/02/from-mobile-home-parks-to-multifamily-housing-cooperatives/ August 2, 2021 During her tenure at Northcountry Cooperative Foundation (NCF), Victoria Clark has become an expert at helping mobile homeowners buy the land where they live. In many places, residents of mobile home parks have suffered as park owners sell out to private-equity firms that then jack up lot rents and reduce services. But since 1999, with assistance from NCF, 823 households in 12 resident-owned communities (ROCs) around the Upper Midwest have kept their rents low, invested in infrastructure, made decisions democratically, and enjoyed the pride of ownership. “We’re essentially providing assistance to small cities. They maintain their own roads, water, sewer, electrical. I mean, holy cow,” says Clark, executive director of the Minneapolis-based nonprofit. “Our ROC program is amazing, it works really well, and we’re doing it at scale.” Yet while resident-owned communities help mitigate the region’s housing affordability crisis, Clark thinks NCF could do much more. She notes that Minnesota has one of the nation’s worst racial gaps in homeownership: while 77 percent of white families own their homes, among households of color and Native Americans the rate is 44 percent. For Black families it is just 27 percent. In Minneapolis a city-commissioned study found a shortage of homes affordable to buyers earning below $60,000, and a severe shortage for those with incomes under $30,000. To help address that vast need, NCF is tiptoeing into the field of urban, multifamily cooperatives. Clark and her colleagues have been working with the South Minneapolis tenant group Sky Without Limits, which is in the process of gaining ownership of five apartment buildings after a lengthy struggle with a negligent landlord. NCF is hoping to serve as the group’s technical assistance provider when it sets up a formal cooperative structure. “That’s going to be our first foray into the multifamily world,” Clark says. “It’s exciting for us organizationally because we want to get into this space. We want to figure out how to do multifamily limited-equity co-ops.” ‘LEGALLY, STRUCTURALLY, FINANCIALLY IT’S VERY DIFFERENT … [BUT] ON THE CO-OP GOVERNANCE SIDE A LOT OF IT IS TRANSFERABLE, BECAUSE YOU’RE TALKING ABOUT DEMOCRATIC MEMBERSHIPS AND BOARDS. NCF has also looked into developing senior cooperative housing, and it is conducting a study of naturally occurring affordable housing around the state so it can identify buildings that are good candidates for cooperative conversion, she says. Clark acknowledged that multifamily co-ops differ in important ways from mobile home ROCs. A resident-owned community owns land but not living units, while a traditional co-op owns and maintains its buildings. When a resident-owned community buys a mobile home park, it arranges a financing package and borrows against the land, whereas multifamily acquisitions are typically financed by tenants’ individual share loans in addition to the mortgage. As it enters multifamily organizing, NCF may also have to develop different technical assistance contract terms and funding sources for its work than those used in the standard ROC model. But Clark says the essential work of organizing residents and helping them run their cooperatives is similar in both arrangements, and she believes her organization is well-positioned to add multifamily communities to its portfolio. Along the way NCF will also look to real estate developers and to experts at the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB) in New York for guidance and advice. “We’re doing this in the Wild West of real estate, which is manufactured home communities,” Clark says. “If we can crack this nut that’s so complicated, that has all these layers of complexity because people own their own individual homes, why can’t we do the same type of thing in the multifamily rental world?” Strengthening the NetworkTenant groups have been creating affordable cooperative housing for decades, particularly in New York, and activists have reported a surge of new interest from municipalities, tenants, and local nonprofits in the last few years. Several new limited-equity co-ops (LECs), which are designed to keep rents low and maintain long-term affordability, have popped up around the country. A few cities and states are considering passing laws similar to Washington D.C.’s Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) that would facilitate cooperative conversions. In the past, UHAB worked with local housing practitioners to help create cooperatives in Boston, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Oakland, Des Moines, Omaha, and Washington, D.C., UHAB Executive Director Andrew Reicher says. Some of those co-ops are still operating, but as federal funding declined over the years many of the local organizations that helped create and nurture them disappeared. Restoring and expanding that provider structure is essential to the endurance and growth of co-ops, Reicher says. “Maintaining those groups on the ground [that] can provide ongoing trainings for new board members, help them each year with their budget, help them with an election, making sure they’re in compliance with their regulatory agreements, whatever it is—that support system is really what’s important.” NCF is one of 12 affiliates of the ROC USA Network, a New Hampshire nonprofit that coordinates collaboration among members and helps finance conversions. ROC USA affiliates work in 20 states, and with their ample experience they could play an important role in rebuilding the national support system for housing cooperatives, Clark and others say. “Having the ROC groups, who are providing technical assistance to a cousin sort of co-op, learn those skills and be able to deal with multifamily housing is a great thing,” Reicher says. ROC USA is deeply focused on mobile home parks and is not interested in adding multifamily housing to its brand, CEO Paul Bradley says. But he says affiliates like NCF are welcome to expand and branch out into different areas, and he agreed that their skills are clearly applicable to multifamily organizing. “All of our affiliates are involved in multiple lines of business, so multifamily co-op work would be a new line for them,” Bradley says. “Legally, structurally, financially it’s very different. It operates under a different tax code. [But] on the co-op governance side a lot of it is transferable, because you’re talking about democratic memberships and boards.” Middle-Income Co-opsWhen Brian Eng, a housing developer in Portland, Maine, and UHAB board member, became interested in co-ops a few years ago, his search for partners soon led him to the Cooperative Development Institute (CDI). A ROC USA affiliate in Portland and the largest ROC technical assistance provider in the country, CDI has assisted 53 mobile home park conversions in Massachusetts, Maine, Vermont, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. Maine Cooperative Development Partners’ plans for Douglass Commons include an apartment building with 56 units, and seven buildings comprising 52 limited equity cooperative units. Photo courtesy of Maine Cooperative Development Partners“UHAB has a lot of intellectual capital, but we don’t have a lot of people, so we need local affiliates if this is going to happen,” says Eng, who grew up in cooperative housing in New York. When Eng set out to develop co-ops in Portland, CDI played a key role in bringing the idea to city council and explaining its benefits, he says. “People in Maine just don’t have a conception of a cooperative. It might as well be from Mars, even though it’s not really that foreign.” Eng’s interest stems from watching home prices soar in Portland over the last two decades, due in part to an influx of wealthy new residents from other states. The high prices have forced public sector employees like teachers and police officers to live well outside the city and commute long distances, he says. “Ironically, a lot of people who are part of the public domain in Portland cannot afford to live here as owners. That’s the gap we’re trying to fill. There has just not been the creation of housing within the Portland city limits for people who work for the city,” he says. Eng had started exploring cooperative development after reading about Raise-Op, a pioneering affordable housing co-op in Lewiston, Maine. Through that group he connected with CDI, which has provided technical assistance services to Raise-Op and also works with agricultural and business cooperatives. CDI staffers advised him to speak with a supportive Portland city councilor and made a presentation to council about housing cooperatives. Portland subsequently solicited developer proposals for a set of city-owned parcels and last year selected Eng’s firm, Maine Cooperative Development Partners (MCDP), to build two “missing middle” projects. They are meant for residents who cannot afford Portland prices but do not qualify for more deeply affordable housing support. Eng said CDI has played a key role in the effort so far and he expects the organization will formally sign on as a technical assistance provider, with help from UHAB. CDI and Eng’s firm have already been organizing prospective residents to join the cooperative, including several immigrant families. “The resident support is crucial,” Eng says. “MCDP is not going to be operationally involved after people move in; that’s where CDI is going to play that crucial role.” Creating a Model Even before Eng contacted them, CDI staff had been thinking about moving into multifamily work and were talking with Portland officials about how city-owned parcels could be used to address the need for affordable housing, says Doug Clopp, head of media and governmental affairs at CDI. Council approval of the two projects over competing proposals bodes well for the future of affordable co-ops in New England and beyond, he says. “We’re very excited to see how this project rolls out, and hopefully it’s a model for other cities across the country. It’s a great story about bringing together city resources, federal resources, private sector, and public nonprofits like CDI—that unique collaboration, where everybody’s kind of rowing in the same direction,” he says. “You can build a cooperative, purposeful community in a city facing huge, huge gentrification issues.” Clopp described the movement across New England to create more limited-equity cooperatives and other housing cooperatives as “nascent.” Interest is driven by the experiences of the 2008 recession and the pandemic, along with the “craziness” of the real estate market, he says. Advocates are currently trying to pass a TOPA law in Massachusetts, which already has over 100 housing co-ops of various sizes and types across the state. “Clearly the demand is there, so the question is, who’s meeting the demand?” Clopp says. A model like the Portland project, or Raise-Op’s work in Lewiston, where it has three small multifamily co-ops and is planning to build two more, could also work in other older mid-size industrial cities like Worcester and Springfield in Massachusetts, he says. CDI would bring its deep experience in community outreach and organizing and learn the rest as it goes. “It’s that old expression, you make the path by walking it. Do we know where that leads? We don’t. But you’ve got to try,” he says. Clopp says the organization would have to increase its technical assistance capacity generally. Ideally other nonprofits would also step up with projects and multiply the number of new affordable housing opportunities across the region. “We want to work cooperatively,” he says. “If you had 10 organizations doing this it would be a teaspoon in an ocean to meet the demand. So let’s see if we can put successful models together that can be replicated by anyone.” This article was originally published in MaineBiz by Maureen Milliken

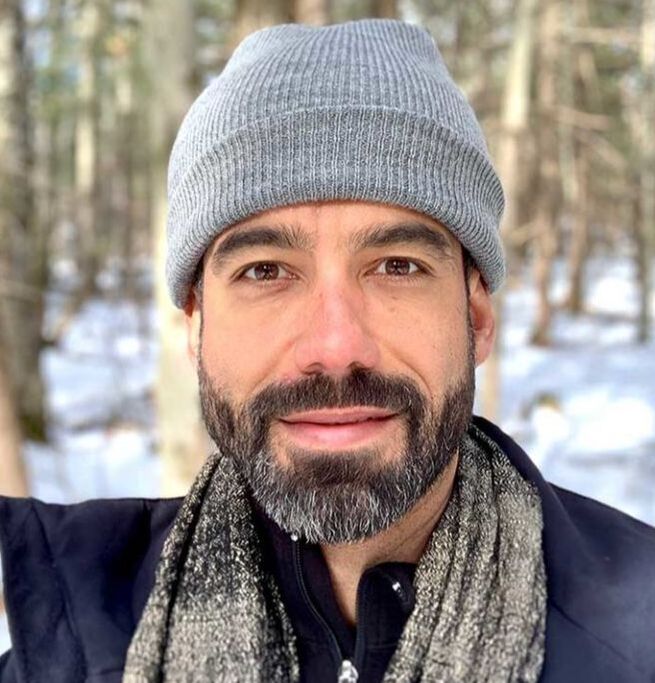

(Caption: A MEREDA Morning Menu panel, from left, Shannon Richards of Hay Runner, who was moderator; developer Brian Eng, of Maine Cooperative Development Partners; and Andy Reicher of the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board, discussed cooperative limited equity housing.) Cooperative limited-equity housing, which could bring more than 100 units to Portland in the next few years, is a model some developers hope will catch on and make a dent in Maine's housing crisis. Brian Eng, of Maine Cooperative Development Partners, said creative thinking to solve the state's housing crisis "is just crucial right now." Eng was part of a MEREDA Morning Menu panel Thursday that also included Andy Reicher, executive director of the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board, which has been developing cooperative housing in New York City for decades. Shannon Richards, of Hay Runner, was moderator. Eng's group is building cooperative limited-equity housing in two Portland neighborhoods. He said that it is not only difficult for area residents to find a home to buy, but employers, desperate for workers in skilled onsite jobs, are finding people turning down a job or rescinding an accepted one because they can't find a place to live. The city of Portland is "very motivated" to find a solution to the area's housing crunch, Eng said. On a larger scale, "It hurts us as a state when people can’t live within communities where they work, or in close proximity." MCDP, which includes Liz Trice and Matt Peters, is developing Lambert Woods, in the North Deering neighborhood, and Douglass Commons, off lower Congress Street. Both will be cooperative limited equity developments. With cooperative ownership, residents own the development, paying shares that cover the mortgage, maintenance and other expenses. In a limited-equity coop, resale value is limited to keep the units affordable in the future. Cooperative housing efforts aren't new to Maine. Some notable projects are the 10 manufactured home communities in the state that are now resident-owned with help from ROC USA, which works with Cooperative Development Institute, and Raise-Op, in Lewiston, where residents of three apartment buildings own 13 units. MDCP's projects are unique in that housing is being built, rather than making a co-op out of existing housing. The Lambert Woods development will have 48 units, and eventually more, and Douglass Commons will have up to 56 small single-family homes in a project that's in partnership with Szanton Co., which is building a 52-unit apartment complex. Eng said the projects specifically target Portland area residents who make between $50,000 and $120,000 a year, but have to rent because they can't afford to buy a house. “It's a very discouraging time to be a household which makes, at least on paper, a very solid income, but can't afford to buy," Eng said. The focus of such developments is home ownership, Eng and Reicher said, not building equity in order to make a big profit on reselling a home. Eng said it's more important for many people to have a stable mortgage over the years, benefiting from a fixed housing cost. "The idea is to build wealth outside of home equity, which is more flexible, more liquid," he said. Reicher said that UHAB's co-ops appreciate 3% a year, so owners know what they'll get if they want to sell in 10 years. "We’re trying to have different perspective on the notion of wealth," he said. When people can afford their housing, it means they can grow financially in other ways, Reicher said. "You actually have disposable income, an opportunity to use unused income to start a business, or go to school, or send your kids to college," he said. "What resonates with me is, how I can build wealth if live an hour from my job?'" Richards said. Things like added day care costs, the extra commuting time, and more, all can have a financial impact. "It adds to the deficit," she said. "This is a chance to own close to a more urban area, and facilitate wealth in other ways." Benefits for state and communityFinancial costs for developing the projects in Maine are supported by the state's Maine Cooperative Affordable Housing Act, which allows limited equity housing ownership, and the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development 213 Program, which insures cooperative housing mortgages. Eng said that while the Portland projects are still in the conceptual phase, they're hoping for a buy-in price for home owners of $10,000 or less. The development group is working with lenders who can support loans of that size to borrowers. In general, Eng and Reicher said, co-ops build a sense of community and the "sweat equity" shareholders put in also helps develop skills that lead to more community involvement, pursuit of education and better job opportunities. Eng said that both Lambert Woods and Douglass Commons also focus on walkability, recreation and community, and will be built to energy-efficient passive house standards. While the focus of his development group is currently on Portland, he said that other parts of the state can benefit as well. One issue is that, for the limited-equity model, there are resident income limits and what their cost is is based on area median income. In Portland, that's fairly high — $70,630 for a one-person household — but it's lower in the rest of the state, making it tough for developers to balance costs. Eng said the group is actively working with people on the state level, given that workforce housing has been identified in the state's 10-year economic plan. "There are are substantial financial gaps" that have to be plugged, he said.  The Maine Cooperative Development Partners is negotiating a purchase and sales agreement for Douglass Commons, where they’re looking to build over 100 units of cooperative housing units and apartments. Matt Peters, left, Liz Trice and Brian Eng of Maine Cooperative Development Partners pose Saturday at the Douglass Street site, the former location of West School, which was torn down in 2015. The Portland City Council has also approved a purchase and sale agreement with the group to develop 165 Lambert St. into at least 20 units of cooperative housing in North Deering near the Falmouth line. Derek Davis/Staff Photographer This article was originally published in the Portland Press Herald.

by Randy Billings Over the last year, the City Council has partnered with two fledgling organizations to develop three city properties into housing cooperatives, which are owned and managed by residents, not a landlord. Fiston Mubalama stands outside a housing cooperative apartment building on Pierce Street in Lewiston on Sunday. Mubalama moved into a three-bedroom unit in the building over a year ago and likes the cooperative ownership model. “With the co-op, it’s way different, because we all look out for each other,” he says. Back in March, Houssein Abdi attended a special meeting to find a way to help fellow tenants whose lives were just starting to be upended by the coronavirus pandemic. They hatched a plan to prevent any tenants from being evicted for nonpayment of rent and to help find additional support for five households struggling to make ends meet. “We came together as an emergency and decided there would be no evictions and there would be no penalties for a person not paying their carrying charges,” said Abdi, 39, who works for the Maine Department of Health and Human Services. But in this case, Abdi and his fellow tenants were also the landlords. And the process they used to help one another was a democratic one, rather than a decision handed down from a single property owner. They are members of the Raise-Op housing cooperative in Lewiston, where residents are directly responsible for managing their property and setting their rents, or carrying costs. It’s a housing model that that has flourished elsewhere in the United States, including New York City and Washington, D.C., but is relatively rare in Maine. That could all change in the coming years, as Portland places a big bet that housing co-ops can help create permanently affordable housing for the so-called “missing middle,” or those who earn too much money to qualify for subsidized housing but don’t make enough to afford market-rate housing. Over the last year, the City Council has partnered with two fledgling organizations – Maine Cooperative Development Partners, which includes affordable housing developer Nathan Szanton, and the Greater Portland Land Trust – to develop three city properties into housing cooperatives. The council last week approved a purchase and sales agreement with Maine Cooperative Development Partners to develop 165 Lambert St. into at least 20 units of cooperative housing in North Deering near the Falmouth line. The group is also negotiating a purchase and sales agreement for 43 and 91 Douglass St., where they’re looking to build over 100 units of cooperative housing units. Meanwhile, the nonprofit Greater Portland Community Land Trust is working on a proposal to build 16 cooperative housing units at 21 Randall St. Urban housing co-ops are relatively new to Maine, but are common in other parts of the county. In the United States, more than 1.2 million families, of all income levels, live in homes owned and operated through cooperative associations, according to the National Association of Housing Cooperatives. They are mostly concentrated in urban centers, including Atlanta, Chicago, Detroit, Miami and San Francisco. Julian Rowand, a cooperative development specialist with the nonprofit Cooperative Development Institute, said there are currently 10 rural housing co-ops in Maine, primarily for manufactured and mobile homes. But Lewiston’s Raise-Op is the only urban co-op in the state. Rowand said Portland’s projects have been years in the making and he expects the model will play a key role in helping to address the city’s housing crisis. “I really applaud (the City Council) for taking this step,” Rowand said. “In the last few years, people have been really interested in this as a way to preserve affordable housing and be able to afford to live in cities. … All states and municipalities need to have this in their arsenal for people to be able to own and to stay” in their communities. Portland Mayor Kate Snyder was one of two council members who opposed awarding the Douglass Street property to Maine Cooperative Development Partners, primarily because their financing strategy would delay construction and occupancy. Instead, she and City Councilor Nicholas Mavodones supported a proposal by Avesta Housing and developer Jack Soley, a team that already had financing lined up to begin their project. “We have very limited experience in Maine with limited equity co-ops,” Snyder said. “When we were contemplating Douglass Street, I knew the development team had already been chosen for Lambert Street and Portland would be given the opportunity to really see how this goes. That was part of my context: How do we do as much as possible as quickly as possible.” Douglass Commons will also generate less revenue for the city and require a greater public subsidy. Avesta offered the city $575,000 for the land compared to $475,000 from the co-op and estimated it would generate $13 million in property taxes over 30 years, as opposed to $3.7 million over 30 years. Douglass Commons will also require additional public support to be affordable. Its budget includes $371,608 in tax increment financing from the city, plus an additional $400,000 in funding from either the city’s housing trust or through its Community Development Block Grant program and another $750,000 in Brownfield funding. City Councilor Tae Chong credited the council’s Housing Committee, led but former City Councilor Jill Duson, for its work on the co-op model over the last few years. Such a housing model will allow people, especially those earning between 60 and 100 percent of the area median income, to gain valuable experience owning and managing their units and building, without having to come up with a large down payment. The area median income for Greater Portland in 2020 ranged from $70,630 for an individual to $100,900 for a family of four. “It’s not a crazy, whacky scheme,” Chong said. “It’s been around for 50 years or more. It’s just new to Maine and new to Portland. And you’re not risking anything. We’re just trying to encourage the missing middle to get a fair chance to be able to stay in Portland and be able to afford it.” The Greater Portland Community Land Trust and the Maine Cooperative Development Partners are using two different models and are in the early stages of planning. Both would put residents in direct control of the management and maintenance at each property. Rents, or carrying costs, would be relatively stable, since the group would just be paying the mortgage on the property and building. But the residents, through a board of directors or homeowners association, could increase those charges to pay for other amenities, like gardens, or build a reserve for maintenance and other capital expenditures. Zack Barowitz, treasurer of the land trust, said his group’s model would be similar to a condominium, where residents would purchase their unit and common areas would be managed by a homeowners association. But sales prices of the units would be more affordable that market-rate condos because the nonprofit will own the land, and therefore not pay property taxes, and will develop the project without charging typical developer’s fees. “You shave a little off here and there and try to make it as affordable as possible,” Barowitz said. The resale amount would also be limited to keep the unit affordable, although the value of the unit will likely increase according to inflation, he said. Details are still being worked out about where that additional value will go: to the owner, to the homeowners association, the land trust, or some combination of both. The Maine Cooperative Development Partners is using a limited equity model. The Lambert Village proposal calls for 20 single-family homes to be constructed during the first phase and 26 additional homes for a second phase. And Douglass Commons contemplates a 56-unit apartment building plus 52 limited equity cooperative units in seven separate buildings. Brian Eng, a developer with Maine Cooperative Development Partners, said residents would need to purchase a share in the cooperative to live at either of its co-ops, rather than purchasing their unit. Early estimates indicate that a share could cost $10,000, though Eng said that number could change based on project costs. And he said it would be up to the co-op members to determine how much they want to allow their shares to appreciate in value. About 20 families have expressed interest in both projects, which still need to secure formal agreements with the city, zone changes and then undergo site plan review and approval, Eng said. “We firmly believe that, working hard on this and doing it the right way, we will be able to offer a home ownership opportunity to people who wouldn’t otherwise be able to access,” Eng said. “We have the ability to target the missing middle. Generally speaking, you end up cooperating with your neighbors more. You end up building communities that can become platforms for personal development.” If Portland’s projects are successful, Eng said the group hopes to expand housing co-ops throughout the state, including Biddeford, Westbrook and Mount Desert Island. The Raise-Op cooperative began in 2008 with a three-unit apartment on Maple Street in Lewiston, according to manager Crag Saddlemire. The co-op began to grow following a string of arsons in 2014, which he said displaced about 100 people and prompted the city to go on a demolition spree. The group operates three buildings with a total of 15 units and is currently raising money to build another apartment building, he said. Since co-ops are managed by residents, Saddlemire said they can also be “a vehicle for social change” in addition to providing affordable housing opportunities. He said that from 2014 to 2017, market rents in the Lewiston Auburn region increased by as much as 35 percent. However, housing costs at the co-op increased only 5 percent, he said, allowing residents to save between $2,000 and $4,000 a year. “At a minimum, it’s their means of affordable home ownership that removes the more individualistic profit-making component of the equation and just focuses on the common need of having safe, healthy homes and trying to save money in the operation of those homes,” Saddlemire said. “It also becomes an organization through which a lot more can be done to benefit the residents and the neighborhood around them.” Saddlemire said the co-op is currently looking to build a new building, which is expected to cost around $3 million. He said the project has broad support in the community, from the more liberal people who see it as a way to foster racial and economic justice to more conservative people who applaud the ownership model and personal responsibility aspect. He’s excited about the projects planned in Portland. “They’ve got a really bold and inspiring proposal and it’s great to see folks take it to that next level,” he said. Saddlemire said turnover at the co-op is low. But nobody has to tell Fiston Mubalama that. He applied for a studio with the co-op when he was 19 years old. Nearly five years later, after updating his application, he was finally approved for a three-bedroom unit on Pierce Street, which he shares with his wife and sister-in-law. Mubalama said all he had to do was put down an $800 refundable deposit to move in, and his rent is currently $785 a month. He no longer needs to harass his landlord to get things fixed. “With the co-op, it’s way different, because we all look out for each other,” the 25-year-old said. Abdi has been living in a building owned by Raise-Op since 2015. At the time, he and his wife were expecting twins and needed a larger apartment. He’s currently paying $766 a month for a three-bedroom place for himself, wife and five children. Abdi said he didn’t know anything about housing co-ops when he first moved in, but has come to value the management structure. His family is part of a strong community. They have more control over maintaining their apartment buildings and the amount they pay monthly to live there. With his wife now working as a nurse, Abdi said his family, which now includes five children, ages 5-13, are looking forward to purchasing their own home with the money they have been saving. “Now that she’s finished going to school and our life is stable, we’re planning to buy a property in one or two years if we find the right property,” Adi said. By Zachary Kussin This article was originally published in the New York Post. Jade Amaker (right) is in contract to buy a $79,000 one-bedroom apartment at 1015 Summit Ave. i n The Bronx, an affordable co-op now home to four of the city's five least expensive listings. Stefano Giovannini Welcome to 1015 Summit Ave., home to four of NYC’s least-expensive abodes for sale.

According to listings portal StreetEasy, prices in the 38-unit building range from a $60,000 studio — which the site lists as the city’s cheapest apartment — to a $75,000 one-bedroom. At least six apartments there have listed since August, offering buyers a shockingly low-priced chance to own property in a city where people go broke to live in a shoebox. “The minute I saw the listing and I saw that there was an open house, I went,” said Jade Amaker, 45, who works in the continuing medical education office at Columbia University and lives in Harlem. In September, she visited a one-bedroom unit in the building, in Highbridge, The Bronx. Just a week later, she submitted her $79,000 offer and is on track to close in January. “I definitely feel like I was on my way of getting priced out of the city, and it was a scary feeling,” said the Bronx native. “I felt like I needed to do something to secure my future in the city and this was it.” Just a 15-minute walk to the subway at Yankee Stadium, 1015 Summit is a Housing Development Fund Corporation (HDFC) co-op, a source of affordable homeownership. Not regulated by the city, available apartments are advertised with income restrictions based on area median income set by individual co-op boards. At 1015 Summit, which is in a low-income area, earnings can’t be greater than $95,520 for one resident and $122,880 for a family of three. HDFC apartments are also intended for long-term living, not investment properties. There are some 1,200 HDFC buildings in the city, which together house about 25,800 units below market rate. Near 1015 Summit, there’s an HDFC co-op where a one-bedroom apartment is listed for $130,000. Meanwhile, in Manhattan, a three-bedroom in an East Harlem HDFC co-op is listed for $850,000, and in Brooklyn, a two-bedroom in prime Williamsburg seeks $625,000. 1015 stands out for its prices well below $100,000. “This is not something that frequently comes up in the market,” said appraiser Jonathan Miller, of Miller Samuel Real Estate. “It is not the norm.” And thanks to those prices, prospective buyers have flocked to the building in recent months to eye its offerings. “[Because of] COVID, it was like, boom,” said Kim McKeller, the building’s Brown Harris Stevens broker. “[People] want to make changes and now’s the time.” Plus, due to a newly formed co-op board, changes are afoot in the entire building, said McKeller. “Owners] want to protect their investment, so they’re doing anything they can” to spruce up the space. There are plans to re-do the lobby, install a grand awning over the entryway and to make storage spaces and a small gym in the basement. Earlier this year, residents added seating and planters to an outdoor area to convert it into a shared yard. “The building had never used the backyard and it blew my mind,” said Fernando Vega, 50, a resident and board member whose work in event production has been hit hard by the pandemic. Along with his husband, Andres Vega, 39, he renovated the outdoor space, which included painting a mural on the cinderblock wall. Vega bought the apartment for $55,000 in 2017, and hopes others will make the decision to put down roots in the co-op even during uncertain times. “It’s … something I’ve been proud of. It’s a big accomplishment and it’s the stuff that dreams are made of,” said Vega. “I have a place in New York City that I want to hold on to — and my forever home.”  A rendering of the proposed Douglass Commons rental and co-op units in Portland’s Libbytown. A rendering of the proposed Douglass Commons rental and co-op units in Portland’s Libbytown. By Dan Neumann Originally published in The Beacon Housing advocates hope that a plan approved this week in Portland will serve as a model for how other towns in Maine can build tenant power, control real estate speculation and create permanent affordable housing. On Monday, the Portland City Council voted 5-4 to approve a plan by Maine Cooperative Development Partners and Szanton Company to build “Douglass Commons,” a limited-equity cooperative housing development, on Douglass Street in the city’s Libbytown neighborhood. The plan calls for the construction of 56 rental units and 52 limited-equity cooperative units, which will be owned collectively by its residents. The plan beat a competing bid by Avesta Housing and developer Jack Soley to create “Douglass Yards,” which proposed 40 apartments, 30 condos and 10 single-family homes. Avesta’s proposal was supported by the council’s Economic Development Committee, but lost after Councilor Belinda Ray submitted an amendment giving the full council the chance to consider the Douglass Commons proposal, which she argued better addressed the city’s urgent need for middle-income housing. Mayor Kate Snyder and Councilors Nick Mavodones, Justin Costa and Spencer Thibodeau opposed Ray’s amendment. Douglass Commons will become Maine’s second multi-unit limited-equity co-op in an urban area. “We couldn’t be more thrilled,” said Brian Eng, a developer with Maine Cooperative Development Partners. “We’re hoping what we put on the table here will get additional governmental support at the state and local level and be something we’ll be able to replicate throughout the state.” A path to permanent affordable housing Cooperative housing is not new. In the early 20th century, many housing co-ops were sponsored by unions to secure housing for their workers. In cities like Washington, D.C. in the post-war era, low-income Black residents were being displaced because of rising housing costs. Housing organizers there rehabilitated old buildings and converted them to resident ownership. Julian Rowand — a specialist with the Cooperative Development Institute and a partner on Douglass Commons — grew up in one of the limited-equity co-ops created in D.C. in the 1970s. “The residents are the exclusive owners of the property. There’s no landlord,” Rowand explained. Members purchase shares in the cooperative, which entitles them to a vote in the governance and management of the building. They pay monthly fees to cover the co-op’s expenses, such as mortgage payments, property taxes and maintenance. They limit equity by placing resale restrictions on the units. This allows residents to build some equity while preventing them from flipping the residence for a profit windfall if the market is hot. “The premise is that housing is a right, not a speculative investment. So, in that way, it’s a decommodification of housing,” Rowand said. Cutting out the landlord and their motive to extract a profit means the co-op operates at cost. Residents are not subject to rent hikes when the landlord wants to match the rising rents of other properties in the area. “The benefits can be pretty substantial. The most important one being that it empowers tenants to have more control over their own economic future,” said Craig Saddlemire, a founder of the Raise-Op Housing Cooperative, a collective of 50 residents including Indigenous people and immigrants who own fifteen housing units in Lewiston. “Being able to participate in making decisions about your housing can provide a lot of stability,” said Saddlemire, who started the co-op in 2008 as a community organizer while a student at Bates College. “Learning how to use the cooperative organization to address your housing situation can also serve as a potential vehicle for even greater social change in the community.” Raise-Op was the first multi-unit limited equity co-op to take off in an urban area in Maine. The co-op model has also grown in rural Maine by converting several mobile-home parks to resident ownership. Saddlemire says the benefits of living in limited-equity co-ops grows over time. While housing may be built today that qualifies as affordable, there is no guarantee that same housing will still be affordable a few years down the road. Limited-equity co-ops, along with public housing, are paths to permanent affordable housing, he says. “From 2014 to 2017, average market rents were going up between 10 to 35 percent,” he said, explaining that three- and four-bedroom apartments likely saw the largest percent increases as those are particularly scarce and sought after by working families. “For us, our operating costs went up five percent over the same time period, which is consistent with what inflation was for that time period.” Housing for the ‘missing middle’ The residents of Sunset Terrace Mobile Home Park in Rockland and of Sunset Acres Mobile Home Park in Thomaston became the seventh and eighth resident-owned communities in Maine in 2016. | Courtesy Raise-Op Portland’s Douglass Commons proposal seeks to fill the dearth of three- and four- bedroom apartments that larger families require, whereas the Avesta proposal sought to create mostly one-bedroom and studio apartments. It also targets middle-income tenants, who until now have been neglected in the city’s affordable housing planning. Douglass Commons set eligibility for incomes between 60 and 100 percent of Portland’s Area Median Income (AMI) — $90,810 for a family of three. Avesta’s eligibility for its proposed units was 100-120 percent AMI. During the bidding process, Maine Cooperative Development Partners learned that none of the nearly 2,000 affordable housing units that the city has approved targets incomes between 60 and 100 percent AMI. Most are under 60 percent with a few in the 100-120 percent range. “That 60 to 100 range is the missing middle. It’s the bulk of working people — teachers, city workers, for example — who want to stay in Portland but really can’t afford it,” Rowand said. “You have this very ironic situation where the people who work for the City of Portland can’t really afford to live in the City of Portland.” Councilor Ray cited this “missing middle” on Monday in her statement of support for the Douglass Commons proposal. Councilor Tae Chong echoed Ray, saying that the fact that 57.1 percent of Portland voters supported the recent rent control ballot initiative indicates a deep concern about the lack of affordable housing in the city. “You buy into the co-op and your rent doesn’t really change. It’s going to be more stable overtime,” Chong was quoted by the Portland Press Herald. “It creates more permanence for more families we’re hoping to attract. We don’t want to lose more kids.” In the past, limited-equity co-ops have been able to grow in other cities as organized tenants pressured local politicians to pass laws such as D.C.’s Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act in 1980. TOPA gave tenants the right of first refusal on their building if their landlords want to sell. Some cities, like Boston, are currently considering similar tenant-purchasing laws. Maine Cooperative Development Partners say they have been contacted by local housing authories in Westbrook, Biddeford and Mount Desert Island interested in co-ops. “I think we are seeing a resurgence of ideas like cooperative housing and TOPA,” Rowand said. “Certainly, in this time of the pandemic, but even before too, issues of displacement, gentrification and affordability have come to the forefront. I think these recent ballot initiatives in Portland prove that there is appetite for this kind of thing with the general public.” Rowand believes local officials must look to what cities like Boston are presently doing, and what other cities like D.C. did decades ago, if limited-equity co-ops are to flourish in Maine. “In many cities, the model has turned into just trying to figure out how to incentivize developers with tax credits to build affordable housing. That has come in the place of working with grassroots housing organizations and supporting them from the ground up,” he said. “Communities in Maine should consider tenant-purchasing laws.” In planning for permanent affordable housing, Saddlemire says that state and local officials must also consider leveling the playing field for self-organized tenants who are forced to compete with large commercial and nonprofit developers for capital and credit. “We need to start creating funding mechanisms that are more friendly towards housing co-ops,” he said. “We’re structuring the programs in a very narrow way that only results in very large rental properties offering a period of affordability which will expire.” Still, with the Portland City Council vote this week, the resident-owners at Raise-Op are glad to welcome new allies in to the cooperative housing movement. “A lot of groups that have been interested in trying to start something but we haven’t seen anyone else get there,” Saddlemire said. “We really want to see the cooperative economy grow.” Top photo: Portland’s Libbytown neighborhood | Corey Templeton, Creative Commons via Flickr Every month PelotonLabs founder Liz Trice interviews a community member for The West End News. This month, to celebrate National Cooperative Month, Liz caught up with Julian Rowand of the Cooperative Development Institute to discuss cooperative housing. How did you get involved with cooperatives? When my sister and I were a year old, my parents were renting in Washington, D.C. and they got an eviction notice. The residents organized to purchase the building and created what became the first Limited Equity Coop in Washington D.C. My mother was the resident manager there from when I was 2 years old until I moved back to DC as an adult and took over her job. So, I grew up in a coop, and that affected my work – community organizing around gentrification and displacement. The people who were my neighbors there when I was a kid are like family to me. People stay for decades in cooperatives, and people look out for one another. We eventually created a federation of limited equity cooperatives in D.C. And then I moved to Maine to work for the Cooperative Development Institute in 2019. How do you help new cooperatives become established? I work primarily with residents in manufactured housing communities, or mobile home parks, when they’re still owned by a landlord who decides to sell. Sometimes they’re retiring, or they’ve heard of us and care about the residents, and they approach us to see if we’d be interested. We reach out to residents and find out if they’d be interested in purchasing the housing community. And then we work with local banks to offer a competitive deal and we facilitate the transaction and train the residents to run the coop. What’s the advantage of cooperative housing vs. renting? When you’re an owner/member/resident, you have a say through democratic governance what improvements are made and whether to increase the rent. Nobody can sell the housing out from under you. As a coop owner, you’re invested in the care of your property and your relationships with your neighbors. Cooperative housing usually becomes more affordable over time because increases are based on actual costs and there’s no external landlord. People are often willing to volunteer on improvement projects, landscaping is a perfect example. People want to come and work on the grounds and the gardens. Could any rental building convert to being a cooperative? Yes. There’s one in Lewiston, Raise-Op coop. Where I grew up in Washington D.C., and in many other cities, that happens regularly. Ideally, Portland and other cities in Maine would enact Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) laws, where tenants have the opportunity to purchase a building that is going up for sale. TOPA requires owners to notify residents at least 30-60 days before the building goes on the open market to give them time to organize and present an offer. With some support, residents can organize and get financing. Massachusetts has laws requiring residents in manufactured housing communities to get notified. And Boston is considering a TOPA law that would apply to rental buildings. New Hampshire has very favorable laws for manufactured housing communities. What does “Limited Equity” mean? Limited Equity means that when you buy in, you pay a low price, and when you leave, the equity stays with the Coop, which is what makes it permanently affordable. Share prices are very affordable. Typically in a normal home purchase you need to have 10-15% of the value in cash. But in our manufactured housing communities the share price is often $100-$400. Something most people can save in a few months. When you buy in, you’re agreeing to be an active member of a community – whether that’s volunteering on the board or on a committee and attending membership meetings. It’s also a different attitude towards housing, considering it more as a right than a financial investment. The cost of living in a cooperative is stable and becomes more affordable over time. So people are able to save and invest money. Are there any new construction housing cooperatives in Maine? There are two exciting new projects in Portland. The city council is voting whether to allow coops on two parcels of city land. One is at Lambert and Washington Avenue Extension and the other is at the former West School site on Douglass Street. It’s an important opportunity because cooperative housing is absolutely essential to addressing housing issues in urban areas. It’s big for residents to have an option to be owners and stay in the city. And it’s also big for the city to make good on its promise to expand affordable housing options. Cooperative housing has the extra benefit of giving renters the stability and governance that homeowners have and making them affordable for generations to come. How can I support the creation of cooperative housing in Maine? You can write or call your city councilor to support cooperative housing at Douglass Street. [City Council’s workshop was on November 5th and their meeting to vote on November 9th.] You can contact Maine Cooperative Development Partners. Or you can contact us at the Cooperative Development Institute. In Lewiston, RaiseOp is a great resource. RESOURCES Examples of cooperative businesses in Maine: https://maine.coop/maine-co-ops/ Cooperative Development Institute: https://cdi.coop RaiseOp in Lewiston: https://www.raiseop.com Maine Cooperative Development Partners: https://www.mainecooperativehousing.com PelotonLabs is a coworking space in the West End of Portland, Maine with a mission to connect and encourage people working on their own to manifest their visions without fear.Tweet

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

February 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed